| Tutorial >> Router Plugins |

|

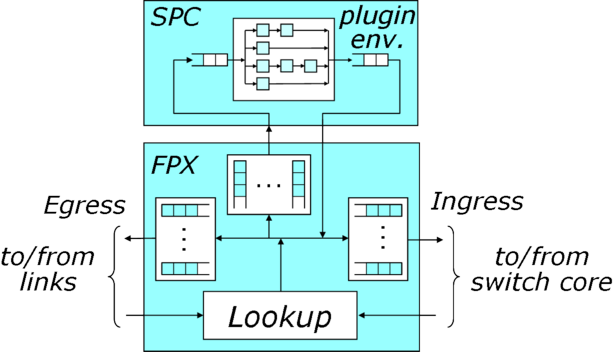

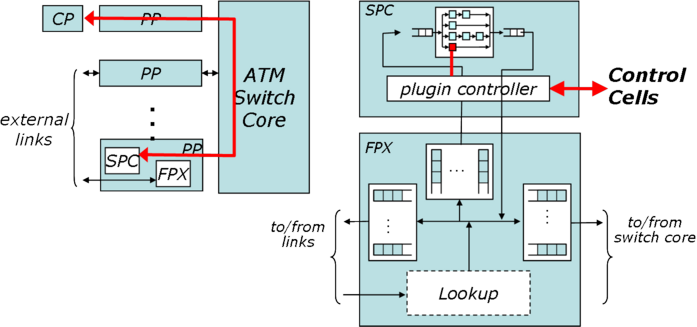

As shown in Fig. 1, packets arriving to a PP pass through CARL, and then normally either enter the switch fabric if from an input link or enter the output link if from the switch fabric. However, NSP users can also direct packets to plugins in the SPC for customized packet processing. A plugin can extend the capabilities of a PP. It can:

The Plugin Framework follows an object-oriented paradigm. A plugin instance (object) has its own local variables (state) and is created from a plugin class. A plugin class serves as a prototype/template for creating plugin instances.

The SPC implements the Plugin Abstraction. Users can:

The plugin abstraction is implemented by the plugin in cooperation with the SPC kernel code. A plugin developer writes plugin code in the C language that defines a plugin class and then compiles the code into a loadable module. The plugin class code performs plugin management, handles packets, and responds to control messages from the CP. In most cases, the plugin management code (e.g., assisting in plugin loading) for an existing plugin class can be used without change in a new plugin class. The control message handling code can be easily customized for most applications. The plugin developer typically writes new plugin code by writing the < Plugin Name>_handle_packet function that handles packets passed to it from the FPX. For example, the function COUNTER_handle_packet is the function that handles packets in the COUNTER plugin.

The RLI provides these plugin management facilities:

A plugin provides the capabilities for extending the filtering capabilities provided by a plugin-free PP. A plugin can be viewed as a filter rule refinement and extension. That is, the plugin can further refine the packet class defined by the filter by providing additional services only to the set of packets it is given that match additional constraints while ignoring the other packets. By definition, the plugin can extend the PP's limited capabilities of forwarding and counting since the plugin can do any of the following:

The plugin code must provide several services:

In practice, most plugins can be derived from standard plugin templates and only the packet handling function must be hand coded.

All of these functions except the packet handling code are initiated as a result of the RLI sending a command to an SPC's Plugin Control Unit (PCU) via the Control Processor (CP) of the NSP. The PCU demultiplexes these commands and effectively forwards them to the appropriate plugin instance by calling the appropriate instance functions. Thus, these instance functions are analogous to object methods in an object-oriented paradigm.

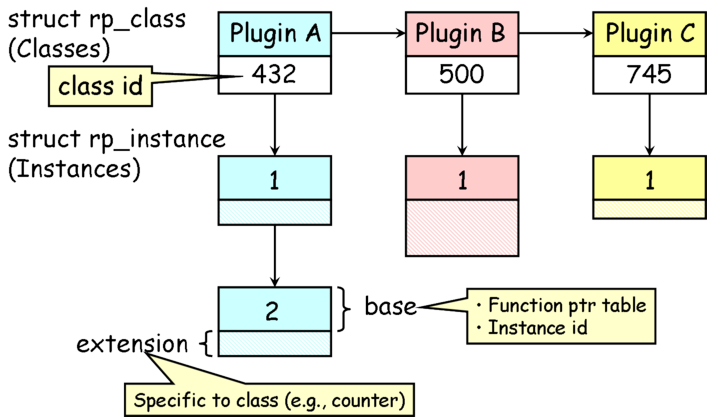

Although you will never have to look at the SPC kernel data structures and control structure used to manage plugins, a brief description of these structures might take some of the mystery out of the plugin framework. Fig. 3 shows the SPC kernel data structures corresponding to three plugins (classes). Plugin A has two instances, and plugins B and C have only one instance each. Kernel memory is allocated for each plugin class and each plugin instance. The storage for each plugin instance consists of a base part which is identical in size for all instances and a customized part (hashed) which can be different for each instance. The base part always has a table of pointers to each of the required service functions (e.g., to handle plugin instantiation). The customized part in a simple plugin, for example, might contain a packet counter and other variables that are specific to the plugin instance.

There is one struct_rp_class structure for each loaded plugin class, and there is one struct_rp_instance structure for each plugin instance. Each plugin class has a user-defined, numeric class identifier. For example, plugin class A has an identifier of 432. This identifier is used by the management subsystem and appears in the plugin source code.

Later sections will lead you through a tour of several plugin modules (e.g., COUNTER, delay, syndemo), and how to write and install a plugin. The COUNTER plugin is described in detail.

| Tutorial >> Router Plugins |

|